One way the Middle East today differs from Moses’ day is that many of its inhabitants descend from Abraham, whom God promised all the Land from Mesopotamia to Egypt (Genesis 15:18). Besides Isaac—Abraham’s son by Sarah—and Isaac’s sons Jacob and Esau by Rebekah, those descendants include Ishmael—Abraham’s son by Hagar, ancestor of the Arabs—and Zimran, Jokshan, Medan, Midian, Ishbak, and Shuah, Abraham’s sons by Keturah (Genesis 16:3, 11; 25:1–6). Many of these descendants of Abraham still live in the Middle East today. In its primal context, therefore, God’s granting Abraham all the land from Mesopotamia to Egypt (Genesis 12:7; 15:18) must account for those peoples also or God’s word would be invalidated. Because at the time God promised Abraham these lands no sons had yet been born to him, God’s pledge was by no means limited to a single nation of his descendants, especially as Abraham was to become a “father of many nations” (Genesis 17:4–5; Abraham 1:2).

Successive guarantees to Isaac and Jacob of the same Land God promised Abraham, however (Genesis 26:3; 28:13; 35:12), changed the dynamics of God’s promise. Without detracting from his word to Abraham, if all the land from Mesopotamia to Egypt was likewise to be the heritage of Isaac’s and Jacob’s descendants, then their connection to the descendants of Abraham’s seven other sons would accord with that of a birthright lineage in relation to its sibling lineages.

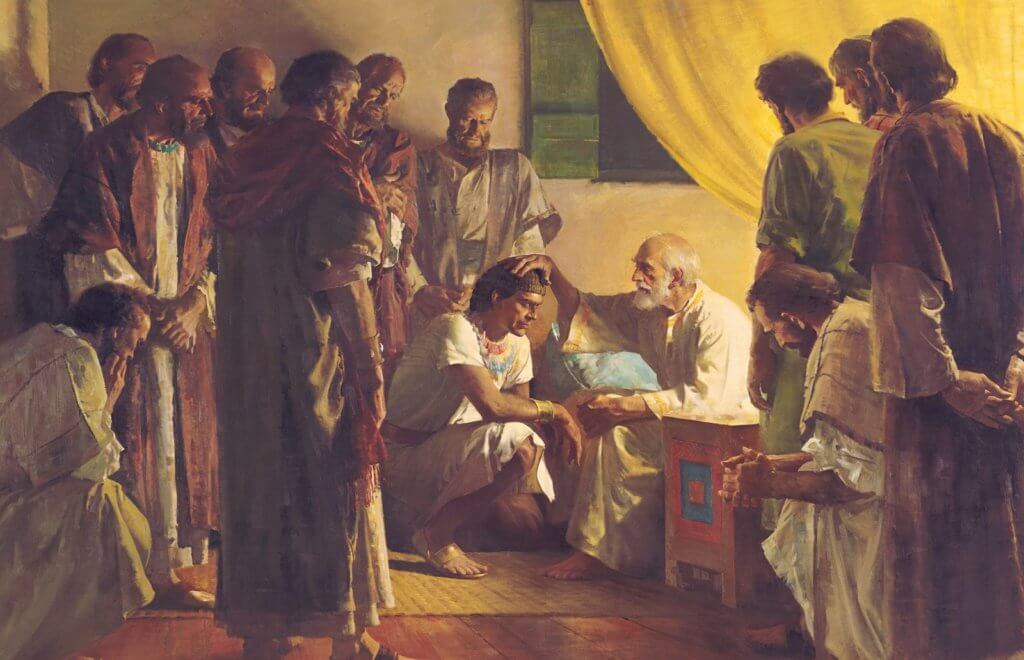

In that case, rather than constituting grounds for banishing Abraham’s other descendants from the Promised Land, Jacob’s descendants inherited the responsibility to be a blessing to them, as was Joseph to his siblings in Egypt (cf. Genesis 28:14; 45:3–7). God’s covenant with Jacob, in other words—of which the Promised Land was a blessing—meant that Abraham’s other descendants’ inheriting the Land would thenceforth depend on their being numbered with Jacob’s descendants so that they likewise might acquire the Land as a blessing.

Although Abraham sent his sons by Hagar and Keturah eastward away from Isaac (Genesis 25:6, 18), the places they settled were within the land from Mesopotamia to Egypt God had promised him. Because Jacob’s descendants subsequently rebelled against him, however, God exiled them to distant parts of the earth. First, Assyria took captive and transplanted Israel’s ten northern tribes to other parts of its empire (2 Kings 15:29; 17:6, 23; 18:11; 1 Chronicles 5:26). Over a century later, Israel’s southern tribes were taken captive into Babylon (2 Kings 24:11–16; 25:1–11).

Although God would turn it to good, Israel’s exile changed the dynamics of God’s promise even more. From then until now, as Jacob’s descendants dispersed throughout the world, many assimilated into the Gentile nations so that today these too can claim Israelite descent. Ultimately, therefore, the blessings of God’s covenant with Israel could extend to the nations of the world by right of lineage, not solely through a process of adoption.

That being the case, Israel’s endtime restoration now hinged on Jacob’s descendants’ fulfilling God’s plan (1) for Israel; (2) for Abraham’s other descendants; and (3) for all nations by renewing God’s covenant and keeping its terms, thus expediting the resumed flow of God’s blessings. Because any digression from God’s design was destined to fail, however, it fell to Israel’s birthright lineage of Ephraim to implement his will as did Joseph in Egypt (Genesis 50:19–21; cf. 48:20; Chronicles 5:2).

Had God not predetermined that from the birthright tribe would emerge “saviors” who would restore Israel just as God had raised up saviors in the past: “In Mount Zion will be deliverance, and there will be holiness. . . . Saviors will ascend on Mount Zion to judge Mount Esau, and the kingdom will be Jehovah’s” (Obadiah 1:17, 21; cf. Nehemiah 9:27; Revelation 14:1); “For there will be a day when the watchmen on Mount Ephraim will cry, ‘Arise, and let us go up to Zion, to Jehovah our God’” (Jeremiah 31:6)?

(From Endtime Prophecy: A Judeo-Mormon Analysis, 50–52.)