Question: Regarding the story of the Prodigal Son in the Bible, I understand the word “Prodigal” is never used. That term was assigned by someone’s using it through time. I also understand that the two brothers represent Judah and Ephraim. Judah has maintained the feasts, etc. Identifying someone as a “Jew” prompts immediate recognition of their culture, religious practices, etc. If you identify someone as an Ephraimite, there is no such recognition other than a tribe. Ephraim will need to be restored as signified in this parable. What is the reference in scripture or learned text that explains the deeper meaning of this well-known parable?

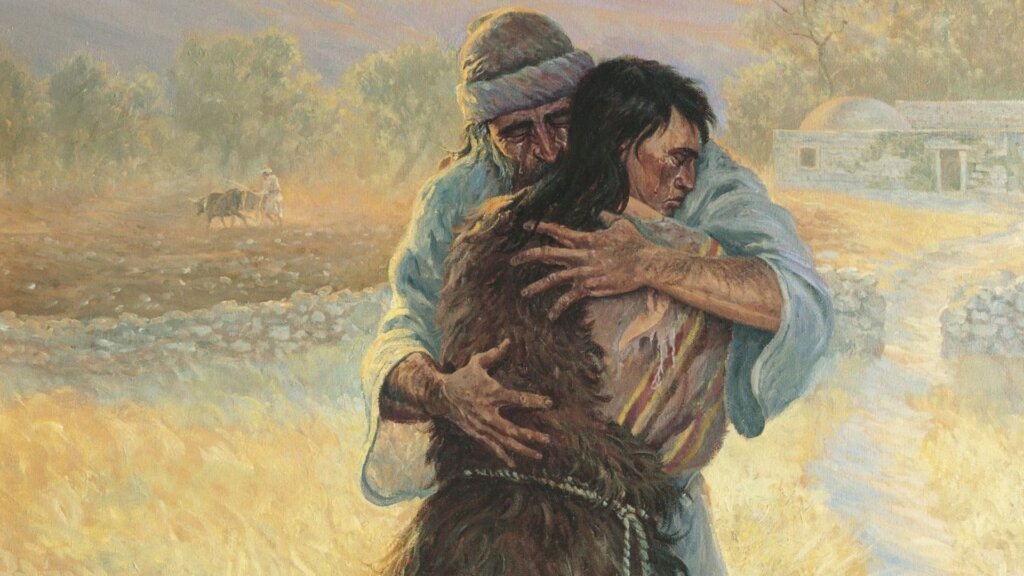

Answer: Although the word “Prodigal” doesn’t appear in Jesus’ parable of the two sons, it does depict this father’s son correctly as a profligate who squandered his inheritance in riotous living. From that being just half the story, Jesus’ parable became a classic paradigm of repentance.

A deeper level of meaning exists in its symbolizing the relationship between Ephraim and Judah, especially in a historical context. However, so does a twin parable Jesus told about a father’s two sons. In Jesus’ second parable, the first son represents Ephraim and the second, Judah:

“A man had two sons. He came to the first and said, Son, go work today in my vineyard. And he answered and said, I will not, but afterward he repented and went. And he came to the second and said likewise. And he answered and said, I go, sir, but he went not” (Matthew 21:28–30).

In each parable, one of the sons excels in accomplishing his father’s will. Summing up their meaning—and comparing it with scriptural history from the time of Jesus—we might say that Judah is the one who starts off God’s plan of salvation, but Ephraim is the one who finishes it.

Accordingly, in the parable of the Prodigal son the eldest son inherits all the father has, symbolic of those saints who inherit all the Father has (Doctrine & Covenants 76:55). The youngest son’s undergoing a descent phase, on the other hand, leaves room for his experiencing an ascent phase.

Another scripture indeed anticipates that: “The richer blessing upon the head of Ephraim,” while “they also of the tribe of Judah, after their pain, shall be sanctified in holiness before the Lord, to dwell in his presence day and night, forever and ever” (Doctrine & Covenants 133:34–35).

Ephraim’s history reflects these things. An entitled tribe (Judges 8:1; 12:1–6), it split off from Judah, mingled with the Gentiles, and worshiped idols (1 Kings 12:16–33; Hosea 7:8). But the Lord’s end-time servant succeeds in reuniting the two (Ezekiel 34:15–28; Isaiah 11:10–14).